What do I care about Middle Chinese?

You probably know the kanji came to Japan from China. But you may not know that, when writing was first introduced to the islands, the Japanese adopted not only the Chinese writing system, but also the Chinese language itself. The first written language of Japan was not Japanese—it was Chinese!

The historical variety of Chinese usually known as Middle Chinese had an especially huge impact on Japan. Around half the words in the modern Japanese lexicon are derived from Middle Chinese roots, dating back to around the time of the Tang and Song dynasties (ca. 800-1200 C.E.).

Despite from what you may have heard, the kanji are far from being a purely ideographic script. They were designed to represent the sounds of Chinese. So it follows that, in order to fully understand the kanji, you need to learn at least a little about those sounds. To this end, in Kanjisense, kanji are presented with romanized Middle Chinese readings alongside the Japanese on'yomi readings derived from the Chinese.

The hidden logic behind kanji readings

The Middle Chinese readings shown throughout Kanjisense aren't there for you to memorize. Rather, they're there to help answer some questions that might arise as you start noticing some patterns in kanji and their on'yomi, like the following.

- Why do some kanji have slightly varying on'yomi?

人 can be read as nin or jin, 女 can be read as nyo or jo, 入 can be read as nyū or jū, or even ji, etc. - Why are the on'yomi all sort of similar?

They're always one or two syllables long, and the second syllable is always ku/ki or tsu/chi, etc. - Why do so many kanji stand for the same sound?

Why should 口, 工, 交, and 高 all have the same reading kō? - Why do so many sound components stand for the same sound?

In the character 校 school, the sound component 交 gives the reading kō. But in other characters with the same reading kō, the sound component is 工, as in 紅 red, 功 achievement, 項 paragraph. So why can't we just write 校 school with the simpler sound component, like 杠?

Of course, none these questions are central to learning Japanese. If you try posing them to a Japanese teacher, they will likely tell you, That's just how it is! and have you go back to grammar and vocabulary drills. But knowing the reasons behind these patterns can help to reveal the hidden logic behind some of these knottier parts of the Japanese writing system.

If you're interested in knowing the hidden logic behind the on'yomi, the key lies in the ancient sounds of Chinese. Knowing even a little about them helps to illuminate the relationships between characters, on'yomi, and sound components.

What's more, if you have any interest in learning modern Chinese, these patterns can also help you understand the relationships between Japanese and modern Chinese words. In fact, the same goes for Korean and Vietnamese, as both of those languages take around half of their entire vocabularies from Chinese, just as Japanese does. In other words, by answering these questions, you can gain the ability to take any Japanese word written in kanji and guess how it's pronounced in Chinese, Korean, or Vietnamese! (This can work vice-versa, as well.)

The Chinese origins of on'yomi

The first step to understanding all these quirks about the kanji and their on'yomi is to realize the following:

- The on'yomi are Japanese corruptions of Chinese sounds. Just like the more recent katakana loanwords borrowed into Japanese, the on'yomi represent Japanese speakers' attempts at pronouncing foreign words within the comparatively tight restrictions of their native sound inventory.

- The Japanese language has changed over the centuries. This shouldn't come as a surprise; all languages change over time. Since the on'yomi were imported into Japanese so long ago, we can't understand them without also understanding the gradual shifts in Japanese pronunciation over the centuries.

Modern Chinese vs. Japanese on'yomi

Knowing that on'yomi readings come from Chinese, you might think that the logic behind the on'yomi would become clear, if only you spoke Chinese. But if you happen to speak a modern Chinese language like Mandarin, you'll know that this is not necessarily the case. In fact, Chinese speakers learning Japanese may find themselves perplexed by different questions:

- Why do some Chinese characters with different pronunciations have the same pronunciation in Japanese?

The characters 口, 工, 交, and 高 are all pronounced kō in Japanese on'yomi, but they are pronounced kǒu, gōng, jiāo, and gāo respectively in Mandarin. Only the first one sounds anything like the Japanese pronunciation! - Why do some Chinese characters with the similar pronunciations have wildly different pronunciations in Japanese?

For example, the character 雪 is pronounced xuě in Mandarin, and 学 is pronounced xué. The consonants and vowels are exactly the same. But in Japanese, the corresponding on'yomi hardly bear any relation to one another—雪 is pronounced setsu and 学 is pronounced gaku.

These questions can only be answered by going back in time, and looking at the sounds of Chinese during the period when the on'yomi were imported into Japanese.

On'yomi: the katakana loanwards of yesterday?

Now, if you've been studying Japanese for a while, you might already know all this. But unless you've studied some historical linguistics, you may not realize that the processes which led to the divergence of the various on'yomi, the modern Chinese readings, as well as the kanji readings of Korean and Vietnamese happen to unfold according to a highly consistent set of rules. This means that, with a little bit of knowledge of the original Chinese sources of the on'yomi, you can largely predict how any given kanji's on'yomi will sound. Even for those tricky kanji with varying on'yomi, there are often patterns governing exactly how their on'yomi can vary.

You can look at on'yomi in the same way as the many English loanwords in Japanese. If you've been studying Japanese for a while, you'll know that, sometimes, you can take an English word and predict exactly how the Japanese translation sounds. Take a word like computer, internet, or smartphone. If you know how a few patterns, it takes little effort to remember the words コンピューター konpyūtā, インターネット intānetto, and スマートフォン sumātofon. Of course, this only works with words that happen to have been borrowed from English (or another language you happen know), but it's still extremely helpful for a language-learner, especially when you're dealing with words like these that were invented recently. If you're at the beginning of your Japanese studies, and that sounds like some kind of wizardry, rest assured—you will gain this skill soon enough. It's just a matter of being exposed to enough English loanwords for the patterns to become clear.

It's the same with Middle Chinese and the on'yomi. Once you understand the patterns, you can usually predict all the possibilities of how any given character's on'yomi might sound, and thus remember words more easily. The difference is that you probably don't speak Middle Chinese, so the patterns governing the the on'yomi won't easily reveal themselves so readily simply through exposure to lots of kanji. This is where the Middle Chinese reading in Kanjisense come in.

Using Kanjisense to trace the history of on'yomi

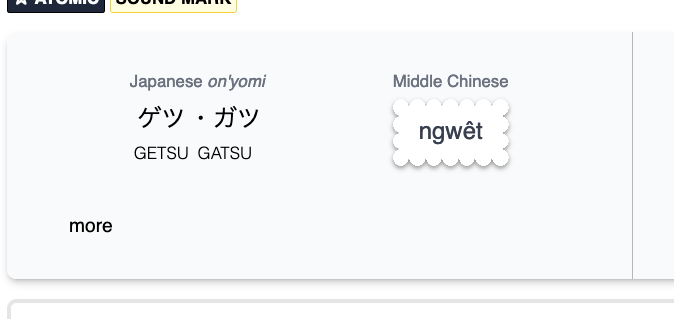

Throughout Kanjisense, you will see Middle Chinese readings near the on'yomi, like this:

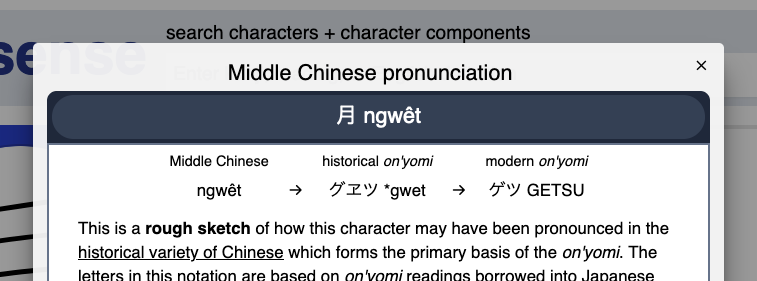

If you click on them, you will find some information about the Middle Chinese pronunciation, and how it developed into the modern on'yomi.

Let's use these to investigate some of the questions we asked above. First, let's take a look at those characters which all share the same reading kō. With this information on hand, can we answer the question of why all these different kanji share this one reading?

| kanji | Middle Chinese | historical on'yomi | modern on'yomi |

|---|---|---|---|

| 口 | kʻouˬ | コウ *kou | コウ KŌ |

| 工 | kōng | コウ *koũ | コウ KŌ |

| 交 | kạu | カウ *kau | コウ KŌ |

| 高 | kau | カウ *kau | コウ KŌ |

(The asterisk marks reconstructed Early Middle Japanese pronunciation. The ⟨ũ⟩ represents a nasal /u/ sound, which was possibly pronounced, but not written distinctly from /u/.)

You don't need to know how exactly how to pronounce Middle Chinese in order to see that these readings are all quite different. You can see for yourself that these readings were all distinct in Chinese, and you can even see exactly how the Japanese of old adapted these Chinese sounds as best they could in their native sound system. Just like with katakana loan words, some distinctions were lost along the way. But still, back at the time of borrowing, these words were not all pronounced exactly the same in Japanese. 交 ⟨kạu⟩ and 高 ⟨kau⟩ ended up sounding something like /kau/, while 口 ⟨kʻouˬ⟩ and 工 ⟨kōng⟩ sounded something like /kou/.

The last piece of the puzzle lies in the sound changes that happened within the Japanese language. These "historical on'yomi" here give you an approximation of the Japanese pronunciation around the Heian period, when a huge portion of the Middle Chinese readings were first introduced to Japan. It's the language of this period that served as the basis of Japanese spelling all the way up until 1945, when the writing system underwent its last major reform. So if you were to take a kanji and write out its on'yomi in kana this way, then you'd end up with something that looks a lot like pre-war Japanese.

This spelling isn't used in everyday life anymore, but it's still something that Japanese people learn in school, when they study classical literature. So an awareness of sound changes like this, where the /au/ became pronounced like /ou/, is actually something that could eventually come in handy, if you have any interest in reading some very old texts.

Of course, I can't pretend like the real reason you should be interested in all this stuff is for some kind of practical benefit—I'll be the first to admit that the practical benefits are few. But when you're learning a language, should it always be about the practical benefits?

On practical benefits

At least for me, a huge motivating factor for learning Japanese has been the experience of getting to know a new culture and its history. A huge part of that is closely observing artifacts of this culture, like the writing system, and asking how they got to be that way. In that process, I find that that the initial fascination, based largely on the allure of novelty, soon develops into something deeper.

Now, instead of simply marvelling at the complexity of these characters, I can appreciate them on another level. Knowing a bit about the history of characters and their readings helps one feel, on an almost visceral level, that this isn't just a writing system; it's an ancient tradition, with roots going back thousands of years. From this perspective, all the inbuilt complexity, or even the impracticality of the Japanese writing system isn't some kind of a design flaw or a hurdle for the learner. It's a testament to the fierce will of a people determined to preserve their history, and to maintain their connection to an ancient civilization that they once looked up to with such admiration.

Unfortunately, people like us who weren't born into a country that uses kanji don't get to grow up with that connection to ancient Chinese civilization, and that makes it even harder for us to learn thousands upon thousands of these characters. But on the other hand, all the work we put into our studies goes into forging our very own, brand-new connection with ancient China—one that's maybe all the more personal, because it was not inherited, but earned. That doesn't make the work itself any easier, of course. But at least in some sense, doesn't it make the work all the more rewarding?

bạk白 njīt日 ʾî依 sạ̈n山 dzīnˬ盡

ghwang黃 gha河 njip入 khaiˬ海 liū流

ŷok欲 giūng窮 tsʻen千 liˬ里 mūk目

kạngˎ更 dźyangˬ上 ʾyīt一 dzŏng層 lou樓

The white sunlight goes out atop the mountains,

The Yellow River flows into the sea.

To make full use of thousand-mile eyes,

Climb up another storey of the tower.

More on the Middle Chinese notation used in Kanjisense in A Rough Guide to Middle Chinese Pronunciation